Creativity is not just something someone is. Creativity is something that you can be, and train yourself to be.

How can I do this, you might ask yourself! Well, you can start by listening to this episode of Hidden By Design, were we will describe what creativity is, and secondly.. and maybe for some more importantly. The Hidden By Designs three step guide to being creative. (Poorly performed by Martin and Mr. T)

Read the entire conversation here

Martin Whiskin 0:02

You’re listening to Hidden By Design a podcast about the stuff that you didn’t know about design. My name is Martin. And this is

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 0:10

Hidden By Design.

Martin Whiskin 0:11

Nailed it.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 0:11

Oh, yeah. And my name is Thorbjorn. Now, the podcast starts and we should start recording now you’re not recording.

So today we’re going to talk about creativity. And I, I put a little bit of an Easter egg in for you. I didn’t …

Martin Whiskin 0:33

Ow.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 0:34

But there’s two Quotes Of The Day and you have to pick. It’s kind of like a Sophie’s Choice.

Martin Whiskin 0:40

Okay, can I am I allowed to assess them? Or do I have to just pick without looking

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 0:45

that’s up to you, that’s up to you. But But today, today, Martin, you will learn what creativity is, you will also learn what the differences between innovation and creativity. Because these words are being used everywhere, right? It’s like ya have to be creative, and you have to be innovative. And what’s the difference really.

So you will learn also how to be creative and get creative thoughts. And then you, then I’m going to give you the hidden by design three Step Guide to Becoming creative, or being creative, I guess, not becoming being amazing. Yeah. And then, in the end, I hope that we can end up with talking about what clouds can teach us about creativity. And, and so many, so many good things. Is is coming your way.

Martin Whiskin 1:41

I can tell you’re excited.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 1:44

I’m very, very, is. It’s a It’s, um, it’s like, it’s an amazing topic. And it’s like in the end it kinda

I guess, without stealing too much of the show. It one of the

one of the things that’s deep inside of most of us, I believe, at least in me, like whatever you struggle with, in life, the joy of creating something, like for the sake of creating something, I tend to be, you know,

sometimes the inner Thorbjørn, wants to sit in a basement by himself and just create stuff that he doesn’t show to anyone. Because the fear of showing it this is not nice. And so if you could do this podcast as an example, just the two of us never share it with

Martin Whiskin 2:43

Should have said that in the beginning.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 2:45

So so but you know, in the word creative lies creates. And I think that’s why it’s so amazing, right? And all we do is as designers, and as creative people, this is create stuff. And I think that’s, that’s it. So now, I think I opened the lid a little bit, but not too much.

Martin Whiskin 3:13

Let’s do the quote of the day, I’m gonna pick the first one, because it’s longer and it gives me more airtime

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 3:25

is that because it showed you your air time, the less like when I do the transcripts?

Martin Whiskin 3:32

I forgot about that. So creativity is inventing, experimenting, growing, taking risks, breaking rules, making mistakes and having fun. And that is Mary Lou Cook,

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 3:47

Which is an actress from the 20s I think not 2000 and 20s.

I have to get used to that the 1920s. So be hearing that and thinking about that I have like I have a question for you. What do you when I say creativity? What? What does it mean to you?

Martin Whiskin 4:10

This is really interesting for me because I didn’t realize or ever really think about being a creative. And it wasn’t until maybe a year or 18 months ago, I was having a chat with someone. They said do you realize that you’ve always been a creative person or someone who creates stuff. I’ve never analyzed it or thought about it because up until a few years ago, I was employed in a full time position in an office and my hobbies were hobbies yet one was making music. One was photography. And I would do posters and websites and all that sort of stuff for the the bands that I was in mainly. And I see realize that you’ve always done creative things. But because I was employed, I thought that was me. Yeah, that was my thing. I was a worker in the rat race with everyone else. And that’s what I did. But looking back, I’ve thought like you as touching on at the beginning, I’ve always had, or felt the need to be making something

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 5:27

yep,

Martin Whiskin 5:28

whether it’s a song, a photo, and then the editing stage. And now I’m in the great position to be getting paid for doing something creative. And I’m making voices, editing those voices, putting them with music sometimes. And I’m scratching that itch every day. And because it’s my profession, the switch has flipped now, for me,

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 5:55

That’s very nice. That’s very, that’s a very, very nice explanation. what creativity is to you. And so what if I told you that creativity doesn’t exist?

Martin Whiskin 6:07

I’ve also thought this as well. I think, I think it’s, it’s a label to explain, like I said, I think the word make for me is better because creativity has I that’s really creative personnel that’s really creative. That has connotations associated with it of, and this isn’t my opinion, but something that that looks or performs excellently. But creativity can be of any standard, I think, yeah.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 6:42

So and this is interesting. So when I think of, or at least in the past, when I’ve been thinking about creativity, for me, it was creating something new and novel. Right? So you think of a creative person, and you think about a person who is capable of just, you know, create something you didn’t think of right? And I guess that’s, that’s, that’s the second quote, we didn’t. We didn’t touch upon. And so so if you look at creativity from a, from a scientific point of view, it’s, it’s, it’s really it is creating something and it is creating something new. It’s like something you came up with. Right? It just that goes into your definition of well, that when you create something, it’s something you came up with, you’re not just copying what someone else is doing directly.

Martin Whiskin 7:43

Yes.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 7:44

Then the question from a scientific view would be how do you come up with these new things that no one thought about before. And then the second quote was Albert Einstein, which was “Creativity is, seeing what others see and thinking what no one else thought.” And that really also frames it. So So I think the two quotes together kind of really, really encapsulates everything right? Is inventing, experimenting, growing, taking risks, breaking rules, making mistakes, having fun, and then seeing what everyone else is seeing, and then thinking different thoughts. So if you hold on to that kind of idea, then I think we I can’t remember there was like one episode where we’re talking about the cave. I can’t remember his name.

Martin Whiskin 8:38

That was season one, episode nine.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 8:41

Remember his name? The cave? It wasn’t that episode.

Martin Whiskin 8:44

I just wanted to sound clever.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 8:48

You really had me impressed there for a moment. But we’re talking about this is like, if you sit in a cave and don’t experience like don’t have any experiences, then, you know, the world that you see, and you create stuff from and your understanding of your surroundings. I think it was affordances actually, is is limited. So that was season one, episode two.

I’m not sure. I’m not sure

Martin Whiskin 9:16

I wasn’t even close.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 9:18

Anyways, so the idea that you can come up with something from nothing. And I think that’s what people tend to have this idea. It’s like he’s creative. He’s like, how did he came up with that idea? But actually, if you can I cut it down, is like creativity is bringing something new into existence. That that has value. Because if someone sits in a basement and don’t share it with anyone, they’re not creative. They’re just, you know, doing stuff. But the idea that you can create something new out of nothing is is kind of. It’s kind of interesting, because you can’t. And so what typically happens when you see creative people is that they were inspired by stuff, right? So you see this, you see this slide, you see people being able to connect things in different ways that creates something new. The set, does that make sense?

Martin Whiskin 10:22

Yeah, I always go back to the using writing music as an example.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 10:28

Yeah.

Martin Whiskin 10:29

Like, learn. You can learn guitar you can be you could be shown how to play guitar without ever hearing any songs ever. Yeah, it would be weird that you’ve never heard any music. But I think all all musicians are a product of their environment. And this is this probably the same for all, all things that you’ve just been saying. So any music that I’ve ever listened to? is in me somewhere in my memories, and that comes out in the music that I create or use to create? You would never say, Yeah, I’m, I copy such and such a band. I think that because, well, first of all, you’re not allowed to. But I think you can take styles and things. But as I don’t know where I’m going with this, but I’ve always used that the example of music. If you’ve been in a cave, never heard music, and were given a guitar or shown how to play guitar, would you be able to write a song?

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 11:34

I know where you’re going with this? Because I can answer that question as well. And, and so you’re in luck.

So So that’s, that’s kind of interesting, right? So if you talk about music, I saw a program, a documentary about music a few years ago, where they were kind of, they were interviewing people who had brain damage, and then all of a sudden lost their sense of rhythm. Right. And these were musicians, so it was kind of a hard blow. And but what it kind of showed is that all humans is this is part of the reasons why we enjoy music so much is that we are born and live, we are lying in the womb, we have this womb womb. And this is why when you like when you hear calming music, it typically is close to on heartbeats, right? That will calm you down the rates. And so we all have this sense of rhythm. And one of the theories or ideas at least was that sense of rhythm come from that point. And so they interest they were very interested in seeing is like, when is the first child born by a woman who have a mechanical heart that doesn’t go, womb womb And will they also have this joy and sense of rhythm? Or will that not be there, right? So there was a very, very interesting things. So when you talk about music, would that person be able to? Well, if it was, the child was born by a lady, they would probably have some sort of theoretically at least sense of because they that’s the input, that’s the only input they would have. But nothing else, right. And so but that that is really so when you’re talking about music, if you think about looking at the music industry, and looking at all the music that comes out, then you will, you will hear about all of these are these artists copy this one, and this start and intro is the exact same as this one. And there’s some slight amazing stories about different bands making almost identical songs, but in different places where they actually didn’t see each other. And you see this thing also when parents gets children. And I think they’re always so creative, by giving their child a unique name. And then 20 years later, you find out that all of the parents of that area had the same unique idea, right? So you’re kind of starting to see that pattern. And also, when you think of like, if you look at music and naming and all of that being creative, is the key word that that I kind of mentioned before, but its value. So you create something. So creativity is you create something, it’s new, or a new constellation of old ideas or things that you pick up from the world. And it has value. So you have these three things, and it has to have value, right? So if you invent a boot but instead of putting it on your feet, you put it on your hands, right? creative idea, or is it because it doesn’t have value to anyone you just have boots on your hands? Right? Some would call them gloves and maybe that is a good idea. I just absolutely could not come up with an idea that just doesn’t have value. Right so but but but yeah.

I just invented gloves Martin, without really realizing

Martin Whiskin 15:02

nice, well done.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 15:05

And the cool thing about boots on your hands is that also they will keep you as well. Like, and you can do dishes, you know, in hot water without burning yourself. If it’s like if they’re made of rubber, man,

Martin Whiskin 15:19

if you were climbing a mountain and you fell down the mountain, you just end up walking down tumbling, but walking with your hands and feet at the same time. i

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 15:29

Yeah, exactly. So I guess, I guess I’m ruining my point here.

My girlfriend, my wife, my first wife, my ex girlfriend.

We went to a classical concert. And it was, let’s just say modern, and it was two hours of disharmonies it was progressive, I have to say, but it was absolutely horrific. And my, my girlfriend got physically ill, like she felt bad from listening to it. And we were kinda like, it’s like, It can’t go on like this, that harmonies must come at a moment, right. And to me, that is like, and that’s the second part of it. It’s it was new, it was progressive. It was not creative in my mind, because it had no value. It was just noises and sounds disharmonies. And it felt horrible to listen to. So it was not. But you had a lot of people sitting and clapping in their hands as they should. But I was not clapping because it was kind of a poor, like it felt. It was an experience. I don’t know if that’s a good idea. But you are, it’s like you’d see this all the time, like people come up with great ideas that are not really great. They have no value, and no one can use them. And it’s just ugly music, or it’s like that doesn’t sound good. Or paintings that doesn’t work or designs. That doesn’t work. Right? It’s like, if it doesn’t have value is not creative. So so how do we it’s like so, you know, if you go to the area of novelty, right? Just something being novel doesn’t mean that it’s creative. Just just like just means that it’s new or different. But to be truly creative. It has to be valuable, it has to carry some sort of value. And then maybe it doesn’t carry value to everyone. The classical concert. Apparently someone liked it. I did not. So you could put that in if you really wanted to. I doubt that anyone liked it. But you know, that’s just me. But but you have like, these are the things and the idea that something is novel doesn’t mean that it’s creative, but it can’t be this. Does it make sense? I’m a kind of out on attention.

Martin Whiskin 18:03

Yes. And for some reason, I was trying to think of something that you would say, oh, that’s novel, isn’t it? And the only thing the only sort of stuff I could come up with was like, you know, you can buy like practical jokes. And like, for example, a fake poo.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 18:21

Oh, yeah.

Martin Whiskin 18:22

On the floor. And some go, oh, that’s quite novel. And it doesn’t really have any value. Unless, you know, unless you take the value from that being tricking someone or perhaps making someone laugh. But in terms of it being able to provide a service, I guess, is where I’m where I’m thinking. It doesn’t do anything. It’s just and Poo exists and jokes exist is just a

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 18:51

Yeah, but you put poo together and a joke together, and you give it to a five year old or three year old. And to them it has value,

Martin Whiskin 19:00

True, a bad example.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 19:02

But it’s no it’s a good example, because it kind of shows that, that creativity is not just like when you create something, it doesn’t have to be for everyone. It has to be for someone, right? It’s just that’s when you design or you do your voiceover. It’s like it’s it you need to know who is it for because it needs to create value for those specific and then you want to create something new and you base that on things that you already know. And then you create these connections

so in kinda, the scientific world about creativity, you we split things up into something called domains and fields, right. And so to domain is an area like music is an area, my area is games an area like a domain, right? So you have all of these physics is a domain mathematics is a domain, chemistry is a domain. So you have these domains of knowledge, different domains of knowledge. And inside of each of these domains, you have fields.

Right. So, you know, in physics you have quantum physics in actually, you could say entertainment is a domain, and then music is a field and inside of that you have jazz, metal, pop, punk, you have all of these, you know, categories. So, so when you look at it from a big picture, you know, people tend to have the idea that what you create, and being creative about have to be something you can see and feel and smell, right. But it doesn’t. So a programmer can be very creative about the, how they do their code. If you invent Slyke,

Albert Einstein and his theory of relativity is very creative, but you can’t see it. Right. And so one of the things that you see throughout, when people are very creative or create something that has to carry the value for the many, that is seen as new and inventive, right? Then, then typically, it comes from cross domain knowledge and cross field knowledge is, you see something from a different area, or you understand something new or, and and, and you pull something from a place that no one saw you pulling it from, and you use it as inspiration in your own domain and field to create something new. And if that new novel thing had value, it’s Creative.

Martin Whiskin 22:07

So there’s something in there, the cross, almost like the crossbreeding of things, yes, I used to write a lot of jokes. And that’s exactly what you do. There you have your idea or, or even just a word that you want to get into a joke. And you split it off into a diagram with lots of different ideas around it. And you look for things that are related to that original idea. But different, yes. On the outsides. And that’s how you you create a new joke.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 22:37

Yeah, exactly. And there’s observational jokes. And there’s like the punch line. And I think it’s like what you will see in a lot of people that you consider creative, you will see a curiosity as well, right? Because, because that’s kind of like the essence of if you put yourself in your domain, and never get outside a door, you’re creativity will kinda narrow in. So what you will see in, in creativity and creative people is they typically have a curiosity about the world and everything, right? So you put anything in front of a creative person, and they go like, Oh, that’s interesting. Tell me more. And you get the sense of right. So when you were talking before, and you said, it’s like, you were explaining how other people is telling you that you are creative, because you never considered yourself a creative person, that the story you told was all of these different things from different domains and fields within like a specific areas. It just like that, to me was what showed that Martin is a creative person. Not that you wrote music alone, but you dislike doing joke and photography, as you’re kind of mixing websites, you’re doing all of these different things, learning how things work.

And then you combine that into being able to create something new. Right.

Just

Martin Whiskin 24:11

Just Just quickly on, on that, creating something new. Something that I have realized, since being self employed and having meeting lots of different people through different businesses, is you could be talking to, you might think that you haven’t got anything in common or you could never work with someone who is really far removed from what you do. And that’s really not true, because I’ve got a client who I edit her podcast, and we’ve been working together for a couple of nearly nearly two years now. And she works in end of life care. So when people are dying, that’s what she knows about.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 24:51

That’s an aggressive trade.

Martin Whiskin 24:53

Wow, is that it’s a heavy podcast to edit. Let’s put it that way.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 24:57

What’s the podcast called?

Martin Whiskin 24:58

It’s called conversations about advanced care planning, and it’s just about preparing for the end of life basically, you know, that’s a transaction there is I, I had her podcast and the other day, we actually came up with an idea for a voice over artist, and an end of life care planner to produce something together. And I think that’s exactly what you’ve been talking about domains and fields crossing over. And until you have conversations with people, sometimes you might, you might never think about those and never shut off a conversation with someone you think, might not be worth chatting to.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 25:30

Exactly. And, and, and even, it’s like, even one step deeper is the curiosity about it. Right? So your curiosity about what she’s doing. And, and a genuine, I can’t say that, well, how do you say genuine,

Martin Whiskin 25:45

genuine,

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 25:46

genuine,

Martin Whiskin 25:47

genuine,

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 25:47

genuine, like, I learned something about English today, genuine, ginger ale interest in, in that other field and in that other domain with the purpose and intent of learning something new, right? And so, there’s, there’s an old, there’s an old saying, that often gets cut off, right? It’s what is it now? No, master of none,

Martin Whiskin 26:17

Jack of all trades, master of none,

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 26:19

exactly, jack of all trades, master of none. And then the rest of the saying has always been cut off. But the whole thing is, it’s better to be Jack of all trades and master of none than being the master of one. And so it’s kind of funny, because that that wording is like, it tells you something about how if you’re in a big corporation, and and you have to work with a very small area of expertise, right? You become an artist or you become you know, someone who does one thing and you get specialized in it, then in that job, I believe that that you have a responsibility of as a human being of being curious about everything else. Because if you specialize, yes, you become very, very good at it. But you lose your creativity. I don’t know if that makes sense.

Yes.

Martin Whiskin 27:14

Yes. And I’m, I really liked that. Because there’s always talk about niching. In business, yeah, and whether you should do that or not, or be open to other stuff. And I’ve always liked the idea of being open

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 27:30

Yeah,

Martin Whiskin 27:31

to other things.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 27:32

And that doesn’t mean that you can’t create a niche product, and kind of really go into that you’re just like, if you want it to be, if you want it to be creative, you have to kind of think and look outside for inspiration. In order to go there.

I’ll just I’ll explain the difference between because now we didn’t talk about innovation yet. And so because that kind of gets mixed up with, with creativity. And I guess that like, just to explain the word is when when you are creative, and you do it with a purpose of making money off it. In many ways, that’s innovation, right? So you have a business side to creativity. So the intent of of being creative and creative, something new, is to make money. And so that’s why you typically see a company as innovative. But you are not.

Right. But if you have the intent, you know, and the company if your company creates something new, that’s an innovation, right? Does it make sense?

Martin Whiskin 28:44

Yes.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 28:46

So So, and that means that innovation also comes from teams of people. Because it’s a team is like it’s a team effort. It’s a company who does something. And so so but in the essence and the core of it, it’s the same thing. It’s just one have a business side, and the other one doesn’t really typically.

Martin Whiskin 29:05

So does that mean when a band writes a song, so there’s rather than just one song, right? Or there’s like three or four people doing it? Does that make that innovative?

If

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 29:17

If they create, like if they so if, let’s just let’s play with that idea. So So here’s my opinion about it at least. So you have a band, it’s three members, they’re working on a piece of music together. So here’s different routes that they can go, they can make a track or a song. That’s like all of the other songs that they made slightly different rhythms, slightly different, you know, beat different lyrics, obviously. And then you have a new song. In some sense. There’s nothing new to that, right. It’s not really being creative. You’re just writing a song and With the intent of, of making money, right, and you can say that there’s levels of creativity, like the lyrics, you’re picking that out from somewhere. Again, if you’re singing a love song in a country, it’s like, if you’re a country western singer, and you’re saving a long song, Love Song, about your pickup truck. And you know, your girl, you know,

Martin Whiskin 30:26

I’m glad you added girl on the end there because the love story between a guy in a pickup truck and actually, I’ve seen photos. I thought that’s where he was going with it. Don’t Don’t Google that, by the way,

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 30:46

no, don’t google it, it will scar you.

Martin Whiskin 30:50

Very odd.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 30:52

So the thing is, right. So if the band have to be creative, they have to look, they have to look outside, the they have to look outside their sphere or their know, their domain or their field of music, to come up with something creative, in you know, in that music that they’re making, right? Doing something new and creative.

Right, then their innovation is like they create a new audience with a new style, something new, right?

Martin Whiskin 32:31

A new way of making the new sound?

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 32:33

Yeah. So an example would be the introduction of techno right before that, you’d only have acoustic instruments, like instruments, you didn’t have electronic. And so all of a sudden, someone creates electronics. And, and and you have the, what is it called the one that that can measure wavelengths and it makes sounds, and someone who makes music things I’d make sounds, can I use that for something? And they take it and they put it into their music, right? And then the whole shangre of electronic music was created. But there was something someone who did it first, because they took something new that no one thought about before. Everyone knew it was there. It’s been there for you know, I can’t remember 50 years or something. And they just realized, wow, this makes sounds, let’s put it in right

Martin Whiskin 33:31

on this path. I actually saw a clip just before we started recording about the, I guess you would call them an electronic metal prodigy.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 33:41

Oh, yeah.

Martin Whiskin 33:41

And those breaking down one of their songs. And I guess they felt kind of fresh and new at the time when they were coming out because they were like a band, almost. But they had lots of members doing stuff. Not all of them did stuff. They just moved around on stage and whatever. But he was saying in this song, there’s like, I think it was seven, seven or eight different samples from previous songs to make this new sound. So how does that work? If if the band is using bits of pre old songs, to create something seemingly new,

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 34:18

so if they are kind of, you know, some of the first that do that they came up with that idea, and it creates value for some, right? So I could imagine that you pick something from an old song that everyone knows and you put it in your new song. And so it creates some sort of recognizability. And since you’re doing it with electronics, it’s like it’s it’s creative. I think what I’m trying to say is creativity is subjective, right? So you can feel that you’re creative, but it doesn’t if no one thinks that it adds value. It’s not. So so there’s this this idea that creativity is not in a person, it’s between the person and society. It’s like the people around you, that dictates if it is right, because then otherwise we’re back to the boots on the hands. Or, you know, copying someone and presenting it in a new was like it’s, it’s you have to. It’s like it’s a it’s a creative dance like it’s a collaboration between people and and the creator.

Martin Whiskin 35:30

Do we need to move to Chapter Two?

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 35:32

Oh, we absolutely do. But you need to read line three.

Martin Whiskin 35:37

Right.

You are so smart T, tell me the difference between divergent and convergent.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 35:55

Oh, I’m so happy you asked.

So so. So to anyone’s listening, if anyone is listening, we have typically a script and a document of notes that we share. And I put this line in for Martin to read to me.

Well,

Martin Whiskin 36:19

Well, I think script makes it sound too rigid.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 36:22

We are Yeah, no, that’s notes it’s

Martin Whiskin 36:26

the bit about the the guy in his pickup truck was definitely not scripted.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 36:31

Divergent means thinking outwards, it means opening up and collecting inspiration. Inspiration, right. So this is what we’re talking about, when we’re talking about looking at being broad and curious. It’s being divergent. And that’s part of the creative process.

Now convergent means you kind of close down and you start the creative process, you create something. So So and these two, and I think they’re very important. And in a moment, when we get to the three step guide to being creative. These two are very, very important to understand. Because it means that you sometimes have to open up and sometimes you have to narrow down, right? And just think about it like a wave that just goes open up, narrow down, open up narrowed down, right?

So if we go to chapter two, which is about how to be creative, then we have that three step guide. So step number one, oh, wait,

Martin Whiskin 37:41

I was just gonna say step one.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 37:44

All right, let’s do this. So Hidden By Designs, three step guide to being creative.

Step one,

Be curious. Find ways to be inspired, and map this out so that you have dots to connect some things. That’s it, sorry, you have to

Martin Whiskin 38:05

Step two,

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 38:06

Connect the dots, honing in on the probe problem, and look at the dots process. And understand, sometimes doing nothing, like walking or something can’t be the thing to do in the second step. Taking a walk, not just walking, but just like go for a walk without disturbances and stuff.

Martin Whiskin 38:27

Step three,

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 38:28

Express your thoughts in writing and drawing, dance, get feedback, and then you repeat, you go back to step one.

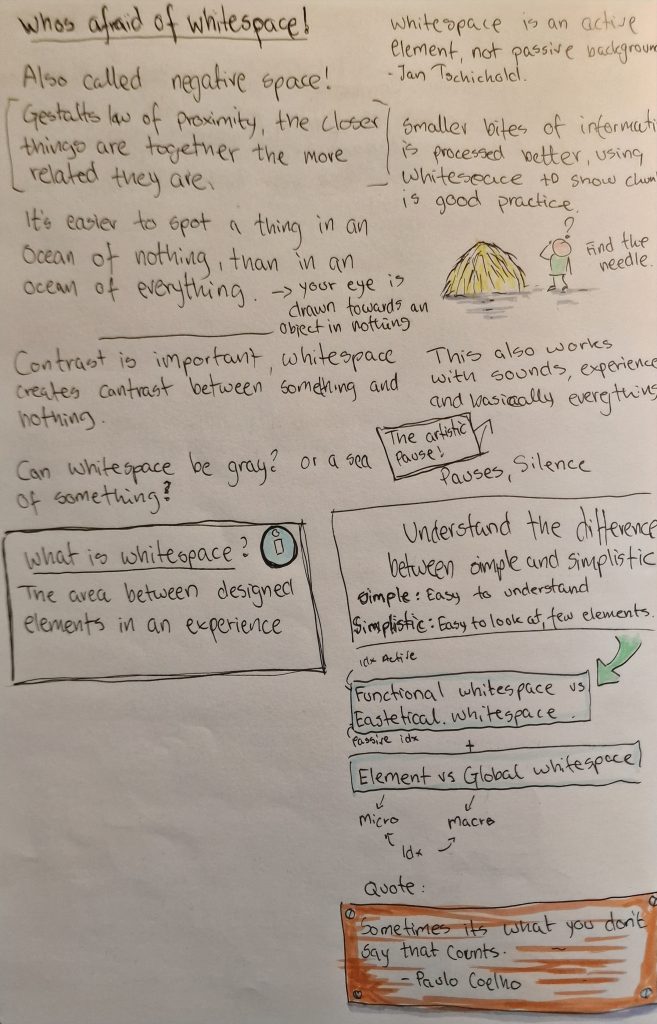

So we’re, like getting that little bit of a mess out of the way is the first step is being curious. That’s the divergent thinking in, in how you and so. So I think I did explain the dots. Clearly, the, the Being creative is connecting the dots between the different domains and fields, right. So you understand something and then the creative process is connecting these things. And you can say each of these knowledges will be a.so. If you look at this as a canvas of different dots and everything, every time you learn something new every time you get inspired everything, like every time you collect some information, you put it on that Canvas as dots in the different domains and feels i’ll upload an image for the episode so you kind of get that where I have a drawing. Now, the first one is to be curious and create as many dots on that Canvas as possible. Anything you know anything like even if you connect two dots from two domains, you put that on that board. It’s like one method that’s popular is brainstorm. Right? You can do that in a group or by yourself a mind mapping or whatever. But it’s kind of a good way of mapping up and remembering all of the things that you know, and is inspired by. So that’s a physical way of doing it. But you can also just do it in your head and go around and just being inspired like picking up and learning things, watching movies, go to museums, is like watch videos about tractors and engineering, like anything goes right, as long as you’re in that mode that you’re collecting and being curious and understanding new domains, right.

The second is, be convergent, like and narrow down and connect the dots actually connect the dots, see if you can find connections between these things. Is Like, is there a connection between playing the flute with your nose, and tractor engines? Right, maybe you can find that connection. Maybe there’s some talents in there that you can use, right? And so classically, you know, you need to sleep you need to be well rested. And part of that being convergent is maybe just going for a walk, reflecting upon it, or thinking about or not thinking about it. And sometimes you will get that moment of realization is like, Ah, very, if I did this, right. And so the the being converting can be also kind of it’s being silent and being reflective and connecting the dots. And then the third one, and this is why, for example, I’m not good at drawing, because my purpose of just like, let me just rephrase that. I don’t draw beautiful pictures, because that’s not my intent of drawing, my intent of drawing is to be able to explain myself, and to explain ideas and concepts. So I draw every day to keep that skill up so that I quickly can sketch out ideas. So part of my creative process is drawing. So I draw, I express my thoughts a draw, like a write down my ideas, or the connections are made in in that convergence. So I don’t forget it. I draw it make drawings, that explains it. And then once that drawing is, is is there, I show it to someone. I say, alright, this idea. This is new, you know, how do you see it? Do you see value in it? Do you understand it? And then people go, Ooh, I don’t understand it. Or maybe they go like, Oh, wow, that’s great, right? And then you go back to the first step again.

And you go, all right, let me just draw a lot of new dots. And at some point, you get to that moment with people say, Wow, man, and so if you go back to the music thing, right. So you collect information, you go around, you listen to sounds, you do cool, you investigate you listen to poems, you, you observe yourself, because you want to write a personal song, you do all of that stuff, it’s part of the the divergent step one. And then the second one, you actually sit down and you try to connect these things, and you, you walk around and your, your thoughts get and then in the end, you write your first piece, right, you were right, the first version of that song and go like, there’s something missing, you go back to step one, and you kind of express yourself. And so that’s a three step guide. And you probably recognize this from you know, design thinking or other people trying to express or explain what creative creativity is, like, how to be how to invent and be innovative and all of that stuff. Right. So, so I guess that was three step guide, clumsily presented by Martin and Mr. T.

Martin Whiskin 43:52

Who put my name first make me sound like a bad one.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 44:02

Skill, luck, talent, being naive, all of this kind of, you know, so the question comes up, do I need to be smart or talent? It’s like what’s, what’s talent and creativity? Can you have a talent for music as an example? Or do I have to be a how do we approach it? And so that’s where naivety is like naivety comes in right? is, when you’re curious? In my mind, being naive is a good approach. Thinking that just like just believing everything you see understanding it because it doesn’t need to be true for you to be creative. So entering a field or domain that you don’t know and talking to people. It’s like having that naive, blue eyed kind of approach to is like, Ah, it’s like new curious word world. And then obviously be

I hope that makes sense. Because it’s it’s not a bad thing. It’s just not a necessity for being creative. Obviously, you have to have some sort of intellect that enables you to understand different fields and understand what people and typically having a broad interest will bring you kind of that knowledge and make you knowledgeable and enable you to create these dots. I hope this kind of makes sense.

Martin Whiskin 46:37

Yeah, for the talented parsing, there’s sort of two ways I’m thinking about that. Yeah. Because you could be a really, really talented guitarist, for example, but unable to write your own stuff.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 46:49

Yeah. And that’s about specialization, I believe. Right. So you can be talented because you really, really practiced and practiced and practiced as you have the technique. But you never bothered to kind of explore that other area. If that makes sense.

Martin Whiskin 47:04

Yeah.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 47:05

So So you have that, you know, being talented. And I think that’s why the, you know, the music, the music part we talked about earlier, right? If I was born by a woman with a mechanical heart, would I be able to understand a beat? Like, would that calm me down? I would that slight would that? Would I associate with that? If if I wasn’t born by a real woman, if I was born in a, in a laboratory, would that Miss? Would I miss that? Talent? Right? And so because you you just like you meet people in your life, do you think oh, that person is tone deaf? They simply don’t have the talent, right? And we’re back to nature and nurture, right? Where does it come from?

So then to end this up, so because I promised that in the beginning is like what do clouds have? Right? What can clouds teach us about creativity? And, and I think I think that’s, that, to me, kind of sums it all up, right? Because when you’re lying there, it’s like, just imagine you’re laying on a field, grass flowers, and it’s a blue sky with fluffy clouds on it. And you’re looking at these clouds, and you see if you can see patterns in it. It goes a little bit back to you know, Gestalt and all of these rules for how we perceive the world. But what happens is that if you look at a cloud and it looks like a dragon, you go, look, it looks like a dragon. And the people around you will be able to see that dragon because they can draw the same reference. But you saw it and they didn’t, right, because you connected the dots, you kind of looked at the shape and you go that looks like that. And another person might see a rabbit. And when they say that’s a rabbit, they’re connecting the dots from you know, an abstract form and, and putting it into something real. So, so you have this thing if someone then says look a submarine and everyone that goes like, you know, there’s no submarine. No one can See it right? Then you’re kind of in the abyss like the area of bizar that doesn’t have value no one can see and connect the dots. And so you can use that like looking at clouds looking at shapes, looking at different things to train your creative mind as well.

I don’t know. It’s like this played out differently in my head Martin.

Martin Whiskin 50:20

Did it sound better in your head? I liked that because it made me think about how clouds are always changing, as well. So you can see new things. Connect connecting different dots all the time.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 50:35

Exactly. Exactly.

And I guess that’s it. Martin

Martin Whiskin 50:41

Nailed it.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 50:44

Today, you learn the difference between innovation and creativity. You learn to how to be creative through and get through to thoughts. And you know, the three step guide to becoming creative, absolutely amazing. Three step guide, right. And then, in the end, what clouds could teach us about creativity? I don’t know the clouds thing didn’t come out as I expected it to. I’m sorry.

Martin Whiskin 51:14

Thank you for listening to another episode of Hidden by design. You can find out more about us at hiddenbydesign.net. Or you can find us on LinkedIn. My name is Martin whisking. This is Toby on Ling God Sorenson net. Yes. Got it. That’s good. You can also like, subscribe, follow the podcast on all of the platforms that’s important to follow it on all of the platforms. Give us five stars. And an excellent review, please, as well. Thank you.

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 51:41

Can I say something?

Martin Whiskin 51:42

No,

Thorbjørn Lynggaard Sørensen 51:42

we love you. I said something anyways, I’m a bad boy.